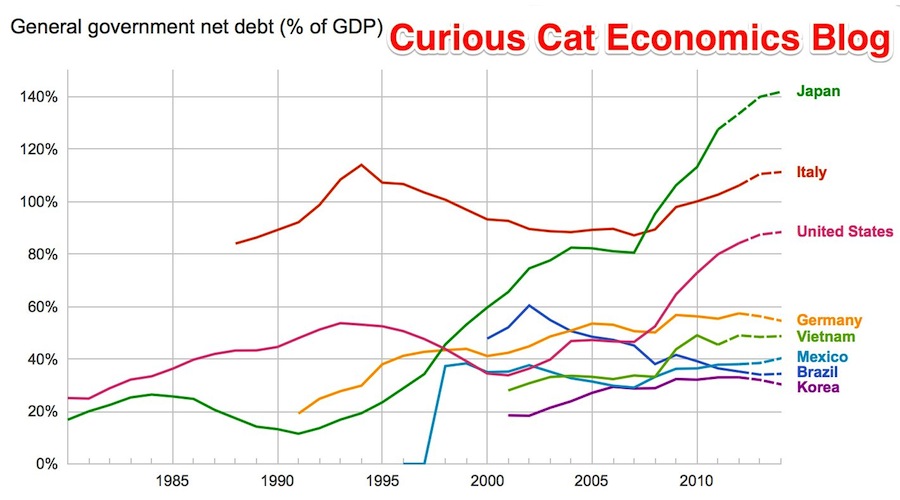

When 2 year US government bonds yield more than the 10 year US government bonds a recession is likely to appear soon. This chart shows why this is seen as such a reliable predictor.

The chart shows the 10 year yield minus the 2 year yield. So when the value falls below 0 that means the 2 year yield is higher. Each time that happened, since 1988, a recession has followed (the grey shaded areas in the chart).

Do note that there were very small inversions in 1998 and 2006 that did not result in a recession in the near term. Also note that in every case the yield curve was no longer inverted by the time a recession actually started.

The reason why this phenomenon is getting so much attention recently is another thing that is apparent when looking at this chart, the 2 and 10 year yields are getting close to equal. But you can also see we are no closer than 1994 and the USA economy held off a recession for 7 more years.

Since 1970 the average length of time from the inversion of the 10 to 2 year yield curve has been 12 months (with a low of 6 months in 1973 and a high of 17 months, before the great recession of 2008).

In addition to a possibly impending yield curve inversion it has been a long time since the last recession which makes many investors and economists nervous that one may be due.

Related: 30 Year Fixed Mortgage Rates are not correlated with the Fed Funds Rate – Bond Yields Stay Very Low, Treasury Yields Drop Even More (2010) – Looking for Dividend Stocks in the Current Extremely Low Interest Rate Environment (2011) – Stock Market Capitalization by Country from 2000 to 2016

Another thing to note about yield curves at this time is that the US Federal Reserve continues to hold an enormous amount of long term government debt (trillions of dollars) which it has never done before the credit crisis of 2008. This reduces the long term yield since if they sold those assets that would add a huge amount of supply. How this impacts the predictive value of this measure will have to be seen. Also, one way for the Fed to delay the inversion would be to sell some of those bonds and drive up long term rates.

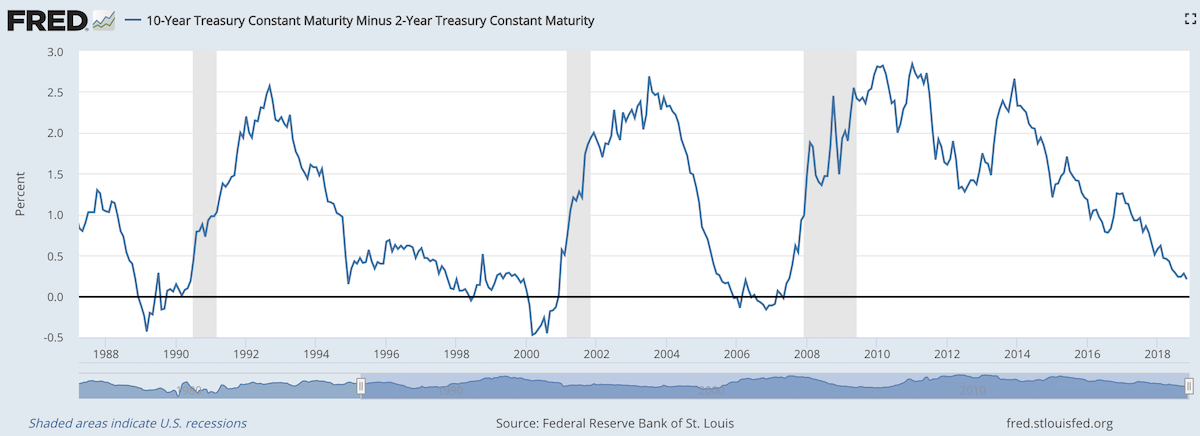

The total stock market capitalization by country gives some insight but it is also data that is a bit muddy. The data doesn’t tell you how the economies of the countries are doing as there is quite a bit of room for misinterpreting the data.

Apple, Alphabet, Intel, 3M, Abbvie… all are included in the USA market capitalization but much of their sales, earnings and employment are overseas. And USA companies have done very well in global markets so the USA totals are not just an indication how the USA has performed but includes great gains made by profiting from global growth. Also you may be surprised to learn that 26% of USA equities are owned by investors outside the USA.

The chart shows the top countries based on stock market capitalization, with data from 2000 to 2016. The chart was created by Curious Cat Investing and Economics Blog may be used with attribution. Data from the World Bank.

It is important to keep in mind the data is shown in current USA dollars, so large swings in exchange rates can have a large impact.

China’s performance has been remarkable. China also shows some of the challenges in collecting this data. I am fairly certain Alibaba (BABA), one of the 10 most valuable companies in the world and a Chinese company has the stock issued in the USA (even this is confusing as it is a complex arrangement but the only publicly traded stock is traded in the USA). And many other Chinese companies are traded this way and therefore are not included in the Chinese total value. In addition Hong Kong is part of China but also separate. The data is reported separately by the world bank and I include them that way in the charts.

As with so much recent economic data China’s performance here is remarkable. China grew from 1.8% of world capitalization in 2000 to 6.9% in 2012 and 11.2% in 2016. Adding Hong Kong to China’s totals shows 3.7% in 2000 with growth to to 12.2% in 2012 and 16.2% in 2016. If you look at my post global stock market capitalization from 2000 to 2012 you will see significantly different historical data for Hong Kong. Collecting this data is much more complex than people realize and data determinations can change over the years resulting in changes in historical data.

The chart shows the 1/3 of the total global market capitalization in order to have the chart display look better (and it also makes it easier to compare the USA performance to the total global performance). The USA market capitalization was at 46.9% of the global market cap in 2000 and fell to 31.6% in 2000 before rising to 42% in 2016. This shows that the USA has largely held its own globally as measured by market cap. This may not seem impressive but when you consider that China has grown from 3.7% to 16.2% you can see that for the market cap outside of China the USA has actually gained quite a bit of ground. This is the result of what I mentioned before – how well USA companies have done at capture global markets (especially in high technology areas with very high profits and therefore very high market caps).

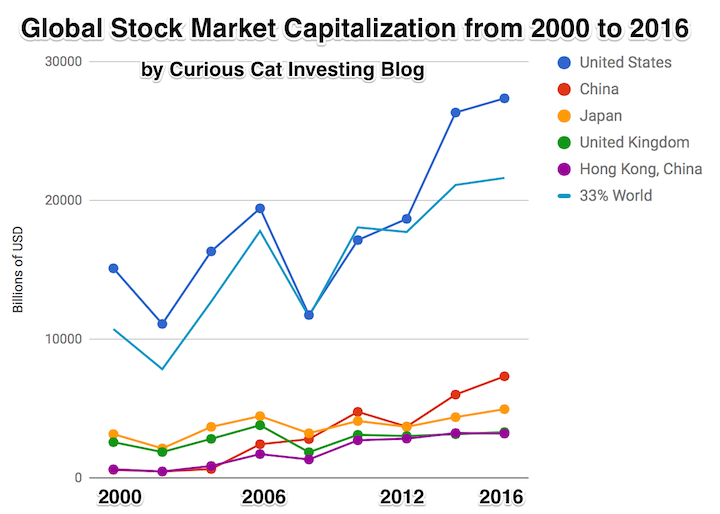

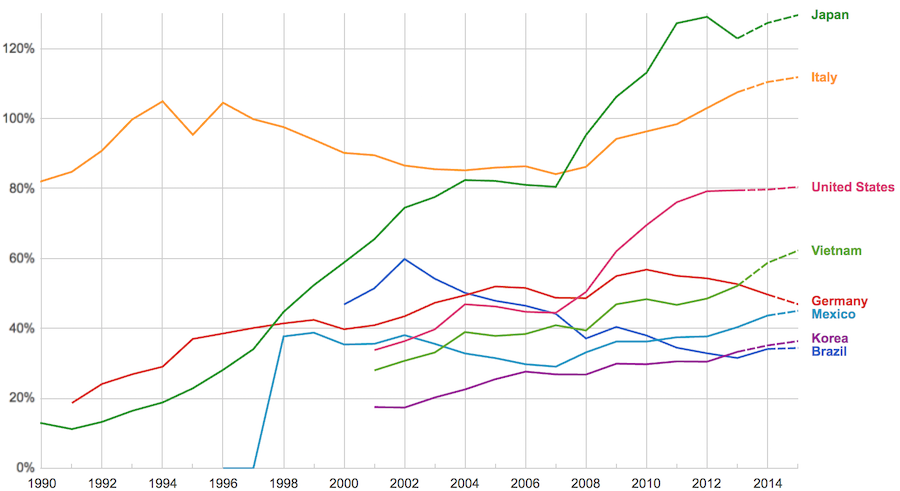

The data, from IMF, does not include China or India.

The chart shows data for net debt (gross debt reduced by certain assets: gold, currency deposits, debt securities etc.).

Viewing our post on the data in 2014 we can see that the USA improved on the expectations, managing to hold net debt to 80% instead of increasing to 88% as expected. Nearly every country managed to take on less debt than predicted (Vietnam took on more, but is very low so this is not a problem).

Taking on debt to invest in valuable resources (building roads, mass transit, internet infrastructure, education, environmental regulation and enforcement, health care, renewable energy…) that will boost long term economic performance can be very useful. The tricky part is knowing the debt levels doesn’t tell you whether the debt was taken on for investment or just to let current taxpayers send the bills for their consumption to their grandchildren.

Also government debt can become a huge burden on the economy (especially if the debt is owed outside the country). The general consensus today seems to be that 100% net debt level is the maximum safe amount and increasing beyond that gets riskier and riskier.

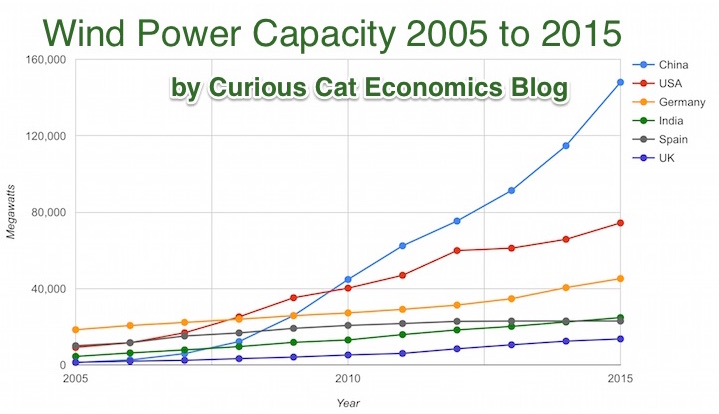

Chart by Curious Cat Economics Blog using data from the Wind Energy Association, data for 2014 and 2015. Chart may be used with attribution as specified here.

After a slowing of additional capacity added in 2013, both 2014 and 2015 saw a bit of a rebound in additions to global wind energy capacity. In 2013 capacity increased only 13% while in both 2014 and 2015 it increased 17%. Still 17% is less than any year in the last 10, except 2013.

At the end of 2013 China had 29% of global capacity (after being responsible for adding 62% of all the capacity added in 2013). In 2005 China had 2% of global wind energy capacity.

At the end of 2015 China accounted for 34% of global capacity, the only country in the top 8 increasing their share of global capacity. The USA now has 17% of capacity. Germany has 10%.

Europe moved first in adding large scale wind energy capacity but has added capacity very slowly in the last 5 years. Germany had 31% of global capacity in 2005. Spain had 17% in 2005 and now has just 5% (during that time Spain has more than doubled their wind energy capacity).

The 6 countries shown on the chart account for 76% of total wind energy capacity globally. From 2005 to 2015 those 8 countries have accounted for between 74 and 77% of total capacity – which is amazingly consistent.

Wind power now accounts for approximately 4 to 5% of total electricity used.

Related: Chart of Global Wind Energy Capacity by Country 2005 to 2013 – Solar Energy Capacity by Country (2005 to 2013) – Nuclear Power Generation by Country from 1985-2010 – Chart of Largest Petroleum Consuming Countries from 1980 to 2010

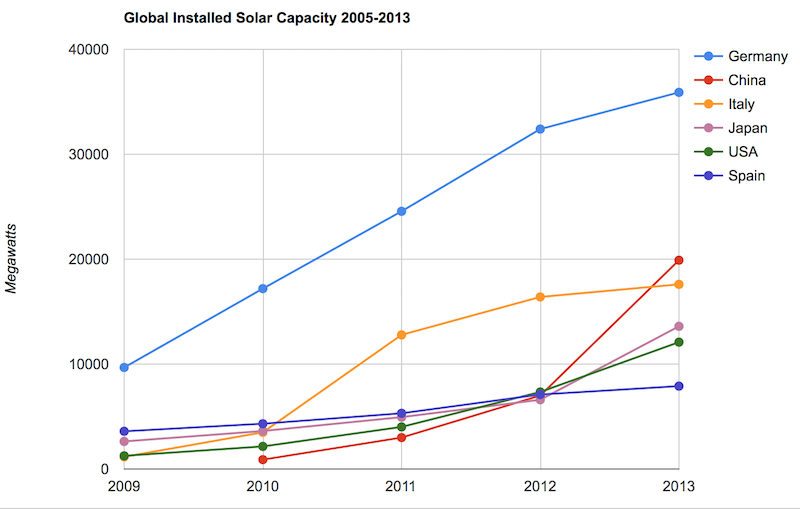

Solar energy capacity has been growing amazingly quickly the last few years. Part of the reason for this is the starting point was so low, making it easy to have large gains.

Chart by Curious Cat Economics Blog using data from the US Department of Energy. Chart may be used with attribution as specified here.

As with so many macro economic measures China has made enormous investments in solar energy the last few years. China’s increase in 2013 was larger than the USA’s total capacity at the end of 2013. Since solar energy use on a large scale is still small investments are quickly ramping up. Europe was a few years ahead of others putting countries like Germany, Spain and Italy far in the lead. China, the USA and Japan have been investing huge amounts the last few years and will likely leave those other than Germany (which already has such a large capacity) far behind very shortly.

In the USA, even after growing 60% in 2008, 53% in 2009, 71% in 2010, 86% in 2011, 83% in 2012 and 64% in 2013 solar energy capacity only totaled 1% of USA total electrical capacity. In 2013 hydropower was 6.8%, wind was 5.3% and biomass was 1.3%. The increase in solar capacity should continue to grow rapidly and is starting to make significant contributions to the macroeconomic energy picture.

When you look at total electricity generation solar only represented .5% (compared to 6.6% for hydropower 4.1% for wind and 1.5% for biomass).

USA data based on only solar capacity that is connected to the grid (and my guess would be that is the measure used in other countries too). Data is largely from that Department of energy report, with historical data for other countries pulled from previous editions.

The US Energy Information Agency (USEIA) expects the USA to add (net) 9,841 MW of wind capacity; 4,318 MW of natural gas capacity and 2,235 MW of solar in 2015. In 2015 they also predict a net decline of 12,922 MW of coal capacity. They also share that nuclear plants and natural gas combined-cycle generators having utilization factors 3 to 5 times those of wind and solar generators, which means capacity measures are significantly different from actually produced electricity measures.

The USEIA has predicted “global solar PV capacity seen rising from 98 GW in 2012 to 308 GW in 2018.” They predicted in 2018 China would have the most solar PV capacity followed by Germany, Japan and the USA.

The Solar Energy Industries Association (USA) states that 5,000 MW of solar capacity was added in the USA in 2013 and 7,000 MW in 2014. They forecast 8,000 MW to be added in 2015 and 12,000 MW in 2016.

Related: Solar Direct Investing Bonds – Chart of Global Wind Energy Capacity by Country 2005 to 2013 – Leasing or Purchasing a Solar Energy System For Your House – Nuclear Power Generation by Country from 1985-2010 – Google Invests $168 million in Largest Solar Tower Power Project (2011) – Molten Salt Solar Reactor Approved by California (2010) – 15 Photovoltaics Solar Power Innovations (2008)

While people question the value of a college degree a recent study by the New York Federal Reserve shows a degree is close to as valuable today as it has ever been. The costs to get that value have risen but even with the increased cost students earn on average a 15% annual rate of return on their investment.

Of course, not every student will earn that, some will earn more and some less.

…

The time required to recoup the costs of a bachelor’s degree has fallen substantially over time, from more than twenty years in the late 1970s and early 1980s to about ten years in 2013. So despite the challenges facing today’s college graduates, the value of a college degree has remained near its all-time high, while the time required to recoup the costs of the degree has remained near its all-time low.

So a college education is a great investment for most people. This can create a problem however, when people then assume that all they need to do is go to college and they will do well no matter what. The same thing happens in other markets. Real estate has proven to be a great investment. that doesn’t mean every real estate investment is good. It doesn’t mean you can ignore the costs and risks of a particular investment. The same goes for stocks.

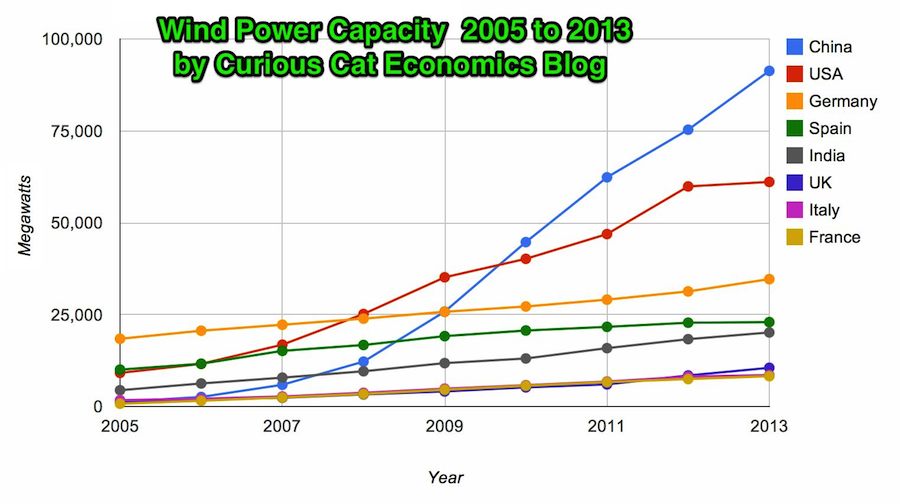

Chart by Curious Cat Economics Blog using data from the Wind Energy Association. Chart may be used with attribution as specified here.

In 2013 the addition to wind power capacity slowed a great deal in most countries. Globally capacity was increased just 13% (the increases in order since 2006: 26%, 27%, 29%, 32%, 25%, 19% and again 19% in 2012). China alone was responsible for adding 16,000 megawatts of the 25,838 total added globally in 2013.

At the end of 2013 China had 29% of global capacity (after being responsible for adding 62% of all the capacity added in 2013). In 2005 China had 2% of global wind energy capacity.

The 8 countries shown on the chart account for 81% of total wind energy capacity globally. From 2005 to 2013 those 8 countries have accounted for between 79 and 82% of total capacity – which is amazingly consistent.

Wind power now accounts for approximately 4% of total electricity used.

Related: Chart of Global Wind Energy Capacity by Country 2005 to 2012 – In 2010 Global Wind Energy Capacity Exceeded 2.5% of Global Electricity Needs – Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment – Nuclear Power Generation by Country from 1985-2010

The data, from IMF, does not include China or India.

The chart shows data for net debt (gross debt reduced by certain assets: gold, currency deposits, debt securities etc.).

Bloomberg converted [broken link was removed] the data to look at debt load per person (looking at gross debt – estimated for 2014). Japan has ill-fortune to lead in this statistic with $99,725 in debt per person (242% of GDP), Ireland is in second with $60, 356 (121% of GDP). USA 3rd $58,604 (107%). Singapore 4th $56,980 (106%). Italy 6th $46,757 (133%). UK 9th $38,939 (95%). Greece 12th $38,444 (174%). Germany 14th $35,881 (78%). Malaysia 32nd $6,106 (57%). China 48th $1,489 (21%). India 53rd $946 (68%). Indonesia 54th $919 (27%).

I think the gross debt numbers can be more misleading than net debt figures. I believe Singapore has very large assets so that the “net” debt is very small (or non-existent). Japan is 242% in gross debt to GDP but 142% of net debt (which is still huge but obviously much lower). The USA in contrast has gross debt at 107% with a net debt of 88%.

Related: Government Debt as Percent of GDP 1998-2010 for OECD – Gross Government Debt as Percentage of GDP 1990-2009: USA, Japan, Germany, China – Chart of Largest Petroleum Consuming Countries from 1980 to 2010 – Top Countries For Renewable Energy Capacity